The Daily Observer London Desk: Reporter- John Furner

A trio of fluid dynamics and mathematical modelers at Kyoto University has discovered how sperm and other tiny creatures are able to skirt Newton’s third law of motion. In their paper published in the journal PRX Life, Kenta Ishimoto, Clément Moreau and Kento Yasuda describe how they analyzed the movement of algae and sperm cells to learn more about how they move so easily through a fluid.

Newton’s third law of motion states that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. Physics students see the law in action by conducting experiments that involve knocking objects together, such as marbles. In the real world, Newton’s third law of motion is often skirted by creatures that have evolved in ways that allow them to conserve energy, which in turn means they do not need as much food to survive.

In this new effort, the researchers noticed that some algae and sperm cells seem to move through their respective fluids with less effort than should be necessary. Such fluids, they note, are typically viscous, which means it requires effort to swim through them. To find out how small cells do it, the team took a close look at them in action.

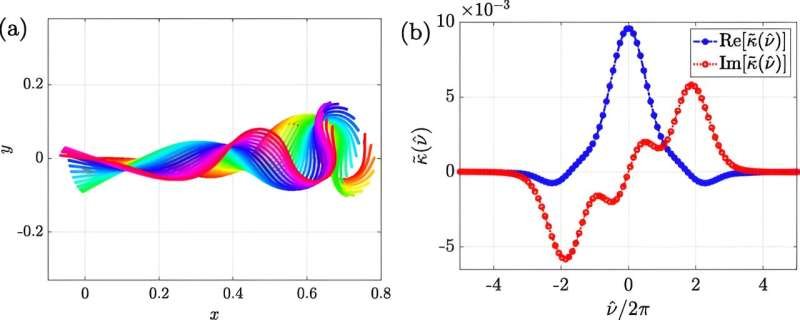

In studying the movement of Chlamydomonas algae and human sperm cells under a microscope, the researchers discovered that both use flagella to mobilize. The hairlike appendages make wave-like movements, effectively pushing and pulling them through their liquid surroundings. Such movements, the researchers note, should result in reactions from the fluid due to Newton’s third law that would greatly slow progress. But that was not the case.

As a sperm swam, they found, it wagged its flagella, as expected. But the team also found that the flagella whipped about in a way that did not lose much energy to the liquid, due to what the research team describe as “odd elasticity.” By bending in tiny ways in response to recourse from the liquid, the flagella were able to avert an equal and opposite reaction, thereby conserving the energy of their owner.