The Daily Observer London Desk: Reporter- John Furner

A small team of physicists and mechanical engineers from Universidad de Antofagasta, Universidad Autónoma de Chile and Universidad de O’Higgins, all in Chile, has found a way to find the stability points of granularly arranged monolayers in a single pile with tilted slopes.

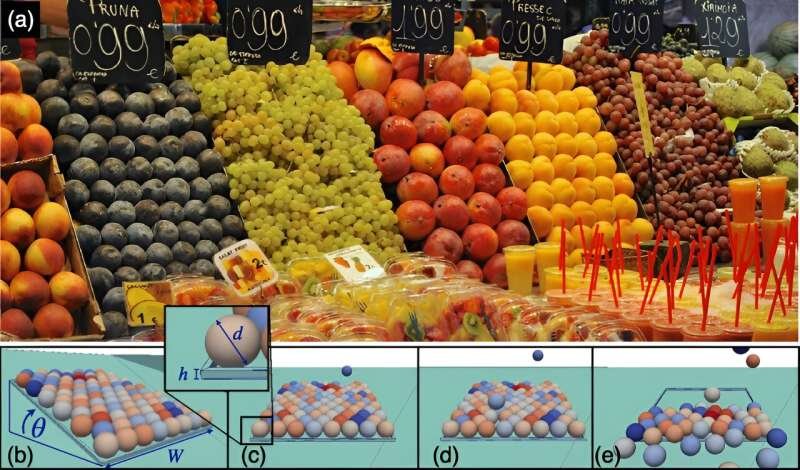

In their study, published in the journal Physical Review E, the group used computer simulations to model spheres, such as oranges, stacked with varying slope edges to discover the point at which the pile will collapse when one or more of the spheres are removed from an edge.

Many grocery stores display fruit for sale by assembling piles aimed at showing off their deliciousness. Such piles tend to have sloped edges, giving an overall image of instability—unwary shoppers who grab a single orange from the wrong part of the pile may set off a collapse with fruit rolling off the shelf and onto the floor. In this new effort, the research team found the tipping points of such piles.

The researchers created simulations depicting piled spheres of various sizes stacked with varying edge slopes and ran them under multiple configurations, from modest slopes to extreme. They found that spheres piled with extreme slopes can indeed collapse if just a single sphere is removed from the sloped edge. They also found that for modest slopes, nearly any number of spheres can be removed without causing a collapse. It was in between such extremes that things became more difficult to predict.

Slowly increasing the slope angle, they found, led to situations where removing multiple spheres rather than just one could result in collapse. They also calculated that under average circumstances, such as those typically found in a grocery store, up to 10% of the spheres (apples, oranges, or grapefruit, for example) must be removed before a collapse. Thus, an individual shopper is unlikely to incite a collapse if they remove just one piece of fruit—unless several shoppers before them have done the same from the same location.

The researchers plan to continue their work, looking into other real-world possible collapse scenarios, such as piles of rocks of different sizes.