The Daily Observer London Desk: Reporter- John Furner

A pair of physicists at Seattle University has found that the path taken by Mexican jumping beans is random and benefits the moth larvae they contain. Devon McKee and Pasha Tabatabai became curious about the movements of Mexican jumping beans and decided to find out if the path they take is directed. They have published their findings in the journal Physical Review E.

Mexican jumping beans are not actually beans; they are seed pods related to spurges. The reason they jump is that moths lay their eggs on the pods. The developing larvae bore their way inside the pod. Once inside, the larvae move around, which causes the pod to move or, in some instances, to jump.

Prior research has shown that the reason the larvae move around so much inside the pod is because they are looking for a cooler place to grow. By moving the pod around, a shady spot can be found, allowing the larvae to grow in a cooler place—if it fails to find shade, it will likely die. In this new effort, the researchers wondered if the larvae had any sort of plan for finding shade or if they just moved around inside their pod willy-nilly.

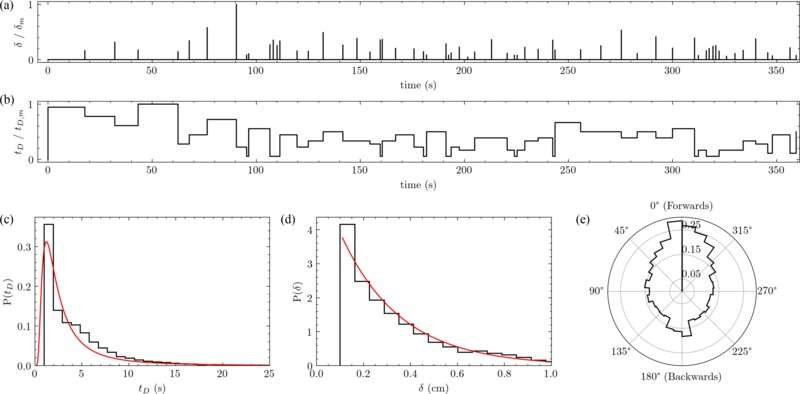

Their experimental setup consisted of a flat recording surface made of heated mats that were then covered with a sheet of aluminum foil to disperse heat evenly. Next, they covered the mats with a piece of ordinary printer paper to make it easier to track the movements of the pods. The researchers also set up infrared thermometers for tracking the temperature on the surface of the paper. Finally, they placed jumping bean specimens on the paper and recorded their movements with a camera from above.

McKee and Tabatabai then used data from the camera to create computer simulations showing the paths taken by the jumping beans. By studying the trajectories of 37 beans, the researchers found that the paths taken were random.

Once they had determined that the paths taken were random, they wondered if that was the best strategy for the bugs. To find out, they compared the random paths taken by the jumping beans with a less random path they generated using the simulator. They observed that random paths guaranteed the larvae would eventually find a shady spot—every spot in a given area would be touched. Using a more directed approach, they found, would be far more successful only if the pods were moved in the right direction—if not, they would never find the shade and would die.