The Daily Observer London Desk: Reporter- Victoria Smith

Once, the word ‘bond’ used to be associated with feelings of reassurance. But recently, some have been recalling the remarks of James Carville, strategist to President Clinton who said: ‘I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as President or the Pope. But now I would want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.’

This was, probably, a humorous comment, but investors have been spooked by events this month in the global market in bonds – the $128.3 trillion worth of fixed-interest stocks issued by companies and governments worldwide to raise funds.

Some UK investors have sold out of bond funds in the past month. This may be a reasoned response to the dire performance of 2022 when the average fund fell by 22 per cent, as Chris Rush of wealth manager Iboss reports.

But if you are thinking long-term, it may pay to note the remarks of Michael Hartnett, Bank of America’s head of portfolio strategy who expects ‘bonds to be the best performing asset class in the first half of 2024, as the fears of a recession starts to recede.’

Recession apprehension and the belief that interest rates will stay ‘higher-for-longer’ sparked a bond sell-off earlier this month, driving up these stocks’ yields – which move inversely with prices.

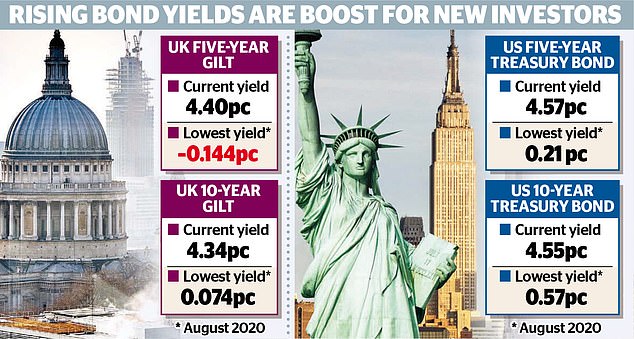

The yield on America’s 10-year government Treasury bonds (T-Bonds) leapt to 4.8 per cent, a level last seen during the global financial rout. In the UK, yields on 30-year gilts rose to 5.1 per cent, their highest since the Asian financial crisis.

This week, yields have dropped a little. In a sudden reverse of sentiment, bonds have regained some of their safe haven reputation. This is the result of the heightening of geopolitical tensions following Hamas’s attack on Israel.

The view that interest rates may not be raised again is also causing yields to ease.

The US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have raised rates to bear down on inflation by discouraging spending. But the view is that higher yields have the same effect, albeit indirectly, as they influence the cost of borrowing for businesses and households.

But even before a measure of calm returned, other experts have been making the case for bonds.

The previously pessimistic Mike Eakins, chief investment officer of Phoenix, the retirement savings giant that owns Standard Life, is shifting into gilts, on the calculation that interest rates could be close to their peak.

Wealth managers are also more upbeat. Haig Bathgate of Atomos comments: ‘We don’t think interest rates will rise much higher – if at all – and so we’re happy to buy and hold and accept the short-term negative sentiment and volatility. You can now lock into a close-to 4.5 per cent yield on a 10-year gilt which looks very attractive on a three-to-five year basis.

‘But corporate bonds are more tricky as there’s a high likelihood that a number of them will default if rates continue at the current elevated levels.’